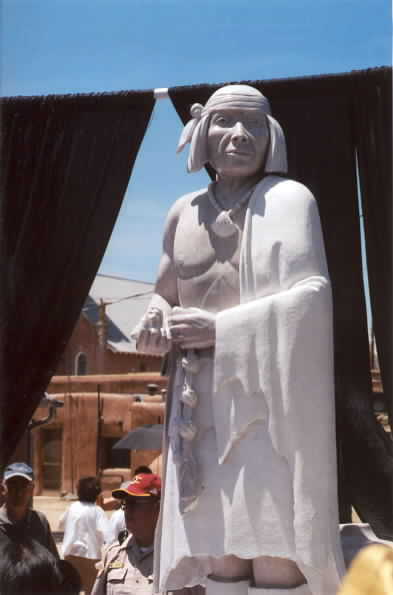

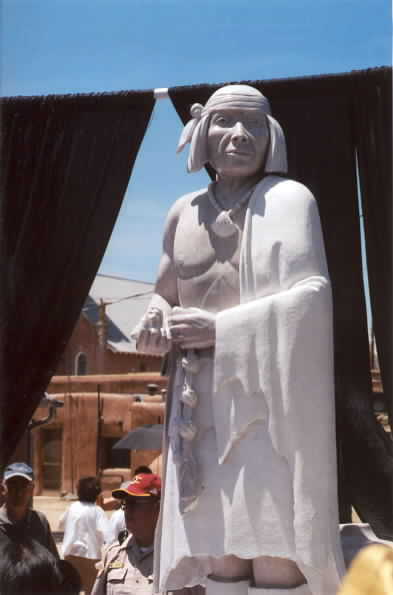

Popé {poh-pay'}

(Tewa medicine man)

Pope's Rebellion

Pope, ca.1630-ca.1690, a celebrated medicine man of the Tewa PUEBLO Indians at San Juan, N. Mex., instigated a successful rebellion against the Spaniards in 1680. Preaching resistance to the Spanish and restoration of the traditional Pueblo culture and religion, Pope led his people in an attempt to obliterate all Spanish influence. On Aug. 10, 1680, the Indians under his leadership killed about 400 missionaries and colonists and drove the other Spaniards south to El Paso, Tex. Pope and his followers then proceeded to destroy Christian churches and other evidences of the Spanish presence in Pueblo territory. Thereafter, as the head of several Tewa villages, Pope exerted what many considered increasingly harsh rule. Dissension arose, weakening Pueblo unity, and in 1692, two years after Pope's death, the Spaniards regained control.

Spanish rule of

the

Pueblo Indians of the Rio Grande valley of New Mexico began in

1598.

Although they numbered 40,000 to 80,000 people at that time, the

many

independent towns, often speaking different languages and hostile

to

each other, were unable to unite in opposition to the Spanish.[1]

Revolts against Spanish rule were frequent, but the Spanish

ruthlessly

repressed dissent. The Pueblo suffered abuses from Spanish

overlords,

soldiers, priests, and their Mexican Indian allies, many from

Tlaxcala,

Mexico. In particular, the Spanish suppressed the religious

ceremonies

of the Pueblo. The effects of violence, forced labor, and European

diseases (against which they had no immunity) reduced the Pueblo

population to about 15,000 by the latter years of the 17th

century.

Po'pay

appears in

history in 1675 as one of 47 religious leaders of the northern

Pueblo

arrested by the Spanish for "witchcraft." Three were executed and

one

committed suicide. The others were whipped, imprisoned in Santa

Fe, and

sentenced to be sold into slavery. Seventy Pueblo warriors showed

up at

the governor's office and demanded, politely but persistently,

that

Po'pay and the others be released. The governor complied, probably

in

part because the colony was being seriously harassed by Apaches

and

Navajo and he could not afford to risk a Pueblo revolt. Po’pay was

described as a “fierce and dynamic individual…who inspired respect

bordering on fear in those who dealt with him.

After his release, Po'pay

retired to the remote Taos Pueblo and began planning a rebellion.

Po'pay's message was simple: destroy the Spanish and their

influence

and go back to the old ways of life that had given the Pueblos

relative

peace, prosperity, and independence. The Pueblo revolt displayed

"all

the classic characteristics of a revitalization movement...the

emergence of a charismatic leader, the development of a core group

of

followers who spread the prophet's message to the wider public;

and,

ultimately the successful transformation of Pueblo cultures and

communities."

Po'pay

began secret negotiations with leaders from all other pueblos.

They

agreed to begin the revolt on August 13, 1680 and runners were

sent out

to each Pueblo with knotted cords, the number of knots

corresponding to

the days left before the revolt was to begin. The revolt actually

began

before that. The measure of the Pueblo's hatred of the Spanish is

indicated that he was able to keep the plans secret, even though

they

involved many different leaders and towns. Po'pay murdered his own

son-in-law, Nicolas Bua, because he feared he might betray the

plot to

the Spanish. Only the Tiguex area, close to the seat of Spanish

power

in Santa Fe and perhaps the most acculturated of the Pueblos

declined

to join in the revolt. The Southern Piros were apparently not

invited

to join the revolt.

"Our

dust and bones.

Ashes cold and white.

I see no longer the curling smoke rising.

I hear no longer the songs of women.

Only the wail of the coyote is heard."

Street Scene, Pueblo of Tewa, Arizona

(click on image for larger version)